Studying Baltimore’s Young Street Trees

Funding: UMD Grand Challenges; USDA NIFA McIntire-Stennis

People involved: Margaret Schaefer, Kelsey McGurrin; Meghan Avolio at Johns Hopkins University; Morgan Grove, Dexter Locke, and Nancy Sonti at the USDA Forest Service; Christopher Swan at UMBC

The more we examine the effects of green space and trees in cities, the more we understand how important they are for the physical and mental wellbeing of the citizens living in urban areas. With this understanding of their importance, it becomes critical to make sure that the trees have a future of continued health, and the services they provide are accessible to all people, regardless of class or race.

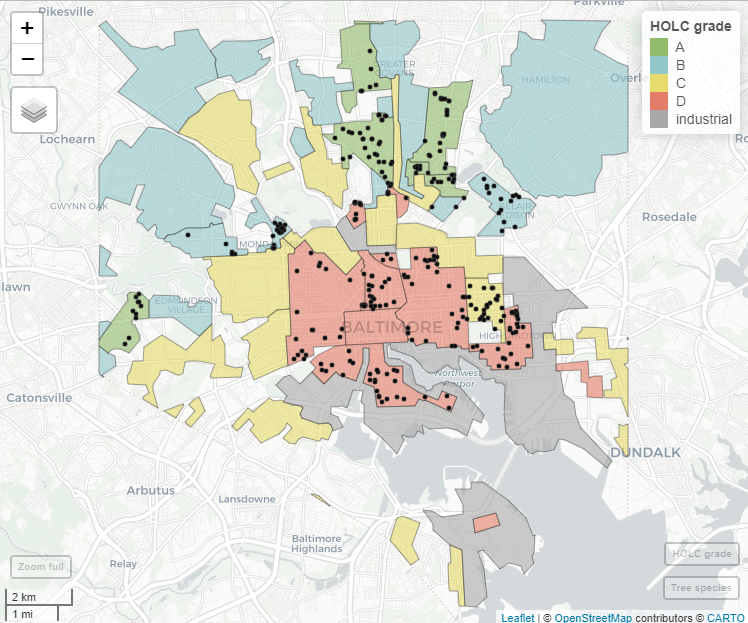

In the 1930’s, many cities, including Baltimore, were divided up by the Homeowner’s Loan Corporation. They ranked neighborhoods by how “risky” areas were to give out home loans, with A being the best and D or “redlined” neighborhoods deemed the worst. These rankings were based in part on the race and immigration status of the residents in the neighborhoods. These rankings have continued effects today, decades after redlining was taken out of practice, because neighborhoods that were determined to be hazardous to loan to in 1937 still have the most human health problems (Nardone et al 2020) and the highest temperatures within a city (Hoffman et al 2020). This redlining effect is also seen in the trees, with smaller trees, less tree canopy, and less species diversity in lower-ranked neighborhoods (Burghardt et al 2022) This is important because the differences in tree size and diversity affect the natural ecological services provided by trees—ultimately impacting the quality of life for residents living nearby. Continued research aims to examine if these redlining effects are impacting tree health and insect populations. The goal of the Grand Challenges project is to look closely at young street trees across the neighborhoods in Baltimore to see if there are current effects to historic racism and class disparity.

Baltimore City has been working to improve tree canopy across the city, with a goal of 40% coverage. However, cities are stressful environments to grow in, as they are often hotter than the surrounding rural areas, and with a history of redlining we know city environments are not homogeneous throughout. We examined tree species across climate predictions released by the United States Forest Service, using their Climate Change Tree Atlas, to see if climate predictions could be used to see which tree species are best suited for the heat and stress of a city. By having a better understanding of which species do best across the temperature gradient of Baltimore, we can make informed planting decisions that will support healthier, longer-lived trees in all neighborhoods, especially those most disadvantaged from past policies.

Sophie McCloskey, undergraduate, and Maggie Schaefer, Master’s student, assessing the health of a street tree. Metrics include height, trunk diameter (DBH), crown vigor, photosynthetic activity, and signs of pests or disease.

Map of neighborhood grades across Baltimore as classified by HOLC in 1937. Street trees sampled in summer 2024 are shown as black dots. We are using a paired design to compare the health of trees from 18 species planted in high (A/B) rated neighborhoods with the same species growing in low (C/D) rated neighborhoods.

Burghardt et al 2022 found that green, low-risk neighborhoods were nine times more likely to have larger and older trees present than red, high-risk neighborhoods. Additionally, trees found in green neighborhoods were significantly more diverse containing more types of trees than in red neighborhoods. (a) Smoothed kernel density estimate of tree sizes (dbh) for each HOLC grade. The dotted lines indicate the dbh cutoffs used to classify “small” and “large” tree designations used for the “old” versus “young” community comparisons. (b) Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) of large and small tree communities. Ellipse denotes the 95% confidence interval for that distribution of points. (c) Reordering and species turnover of large and small trees among HOLC grades. Significant differences (p < 0.05) are denoted by letters.

Selection in the city: understanding the roles of natural and domestic selection in shaping the function and sustainability of urban forests

Funding: USDA

People involved: Eva Perry, Meghan Avolio at Johns Hopkins University; Morgan Grove, Dexter Locke, and Nancy Sonti at the USDA Forest Service.

Trees are long-lived and provide key health benefits and ecosystem services to city residents leading to world-wide efforts to increase greenspace and tree cover in cities. Trees planted in cities face temperature increases (urban heat island effects and climate change) while simultaneously experiencing greater incidences of insect pest outbreaks. Are the trees we are currently planting in our urban forests optimized to withstand these stressors or will the use of genetically identical cultivars and clones selected for traits that humans prefer such as flower number and color decrease the adaptability of urban forests? We are examining whether domestic selection (breeding or nursery/consumer choices) of urban maple trees, Acer spp., changes the genetic structure of remnant urban forests and their resilience and resistance to climate change and insect pests.

Maple trees are popular for their vibrant fall colors, but trees bred for their looks aren’t necessarily the best adapted to city life. Photo credit: K. McGurrin

Early (top) and late (bottom) instar caterpillars of the Rosy Maple Moth, Dryocampa rubicunda, feed almost exclusively on maples. Photo credit: K. Burghardt

To meet our objectives we will be comparing a domestically selected, invasive, exotic species (Acer platanoides, Norway maple) with a domestically selected, native species (Acer rubrum, red maple) in Baltimore, Maryland. We will sample trees along an urban management gradient to find trees which are wild type, F1/F2, or cultivars.